The Anchoring Bias: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and Mitigating Its Impact

Introduction

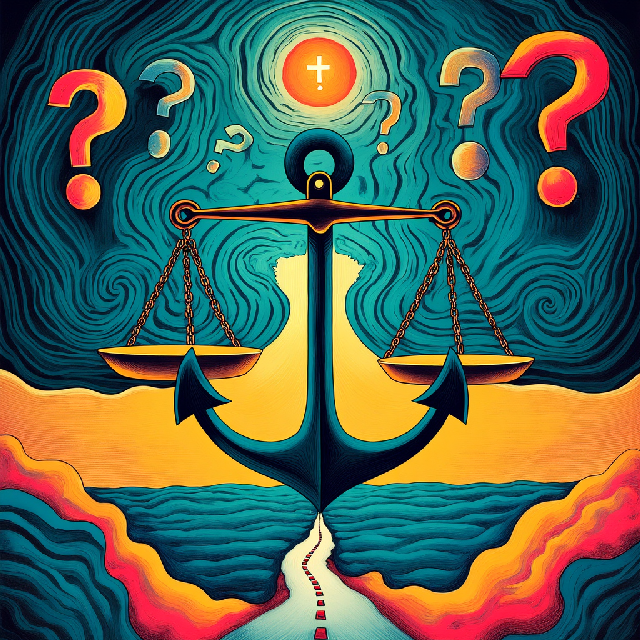

Anchoring is one of the most influential cognitive biases affecting decision-making. It occurs when we heavily rely on the first piece of information encountered—the “anchor”—as a reference point for subsequent decisions or judgments. This initial piece of information often leads to biased outcomes because adjustments made from this starting point are typically insufficient.

How Anchoring Works

The concept of anchoring was first introduced by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s. It is one of the most well-documented cognitive biases, affecting both everyday decisions and complex negotiations. For example, if you see a product priced at $1,200, another product priced at $100 may seem like a bargain—even if it’s not necessarily a good deal.

Anchoring can occur with both numeric and non-numeric information. In numeric anchoring, an initial number sets the stage for future estimates. For instance, if you’re asked whether Gandhi lived to be 140 years old and then asked how long he actually lived, your estimate will likely be higher than the true answer because of the influence of the anchor.

The Psychological Foundations of Anchoring

The anchoring effect is often attributed to insufficient adjustment. When we’re given an initial value or piece of information, our brains tend to latch onto it and make only small adjustments from there, even when those adjustments are logically warranted. For example, if you’re told a mug costs $100 and then offered it for $20, your perception of its value is skewed because the initial high anchor ($100) influences your judgment.

Why Anchoring Happens

- Insufficient Adjustment: People often fail to adjust their initial estimates sufficiently. Once an anchor is set, subsequent adjustments are typically small, leading to judgments that are closer to the anchor than they should be.

- Selective Accessibility: The presence of an anchor makes information consistent with it more mentally accessible. For instance, if you’re asked whether Gandhi was older or younger than 144 when he died (an obviously high and unrealistic number), your estimate will likely be higher than if you hadn’t been given that number.

- Cognitive Load: When we’re mentally fatigued, we rely even more heavily on anchors as a mental shortcut to conserve cognitive resources.

The Impact of Anchoring

The anchoring effect has far-reaching implications:

- Decision-Making: It affects everything from negotiations and financial decisions to everyday choices like buying products or estimating quantities.

- Perception: Anchors can distort our perception of value, size, or likelihood. For example, a store might place a high-priced item next to a more reasonably priced one to make the latter seem like a better deal.

- Behavioral Economics: The anchoring effect is a key tool in marketing and pricing strategies, where businesses use high “anchor” prices to make other options appear more attractive by comparison.

Anchoring in Negotiations

In negotiations, anchoring plays a crucial role. The first offer on the table often sets the tone for the entire discussion. For example, if a seller starts with a high price, the final agreed-upon price is likely to be higher than if they had started with a lower price. This makes being aware of anchoring—and learning how to counteract it—critical in negotiations.

How Anchoring Works in Negotiation

- Setting the Reference Point: The anchor establishes a psychological reference point that frames subsequent negotiations. For instance, if a seller opens with a high price, it sets a higher baseline for the buyer, making any counteroffer seem more reasonable by comparison.

- Influence on Perceptions: People tend to adjust their expectations and judgments based on this initial anchor. Even if later information contradicts or modifies the anchor, its influence persists, shaping perceptions of what’s fair or acceptable.

Effective Anchoring Techniques

- Set High but Reasonable Anchors: Start with a high yet credible offer to leave room for negotiation while influencing the opponent’s perception of value.

- Use Strategic Ranges: Presenting a range (e.g., $80K to $100K) can guide the negotiation within desired bounds.

- Let the Opponent Anchor First: Sometimes, allowing the other party to set the initial anchor provides valuable insights into their position and limitations.

Mitigating the Anchoring Effect

While anchoring is a powerful cognitive bias, there are strategies to reduce its impact:

- Awareness: Recognize when anchoring is occurring.

- Objective Criteria: Use objective standards or benchmarks to evaluate information rather than relying solely on the anchor.

- Counter-Anchoring: Introduce your own anchor to shift the reference point.

- Time and Reflection: Take time to reflect on decisions, especially in high-stakes situations.

Risk Assessment and Decision-Making

Risk assessment is the process of identifying potential risks, evaluating their likelihood and impact, and implementing strategies to mitigate or manage them. Anchoring can significantly influence this process by skewing perceptions of risk and leading to suboptimal decisions.

Tools and Techniques

- SWOT Analysis: Identifies strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to assess strategic risks.

- Risk Heat Maps: Visual tools that prioritize risks based on their probability and impact.

- Decision Trees: Diagrams used to evaluate different courses of action and their potential outcomes.

Overcoming Anchoring Biases: A Guide to Better Decision-Making

Anchoring bias is a natural but costly cognitive shortcut. By staying aware, seeking diverse perspectives, and leveraging tools like AI, you can make more rational, informed decisions. Remember: the first piece of information doesn’t have to be the last word!

Real-Life Applications

- In negotiations, start with a high but reasonable anchor to set the tone for discussions.

- When shopping, compare prices across multiple stores instead of focusing on the first price you see.

- In investing, avoid making decisions based on a single data point—consider long-term trends and expert advice.

Conclusion

Anchoring is a fundamental concept in psychology that has far-reaching implications for decision-making, negotiations, and everyday life. By understanding how anchoring works and implementing strategies to mitigate its effects, we can make more rational, objective decisions and avoid the pitfalls of this cognitive bias.

I’m curious if the article includes specific examples of studies that show how well counter-anchoring works in real-world negotiations. This could make the practical advice more convincing.

Thanks for pointing that out, @Goldie. The article discusses counter-anchoring but lacks concrete examples from real-world negotiations. While it references Tversky and Kahneman’s foundational work, including empirical evidence from negotiation studies would better demonstrate how these techniques apply in practice.

Thanks for pointing this out! Adding real-world examples would make the advice more practical. To improve the article, briefly explain what counter-anchoring is and include two or three recent study examples where this strategy worked well in negotiations. This will help readers understand how to apply it themselves.

The article clearly explains anchoring bias but lacks studies showing counter-anchoring’s effectiveness in real-world negotiations. Adding specific examples would help demonstrate how well this strategy works in practice.